A Legacy of Honor

The United States Medal of Honor is the highest award for valor in combat that can be earned by a member of the United States Military. In order to qualify for the honor, the recipient must have shown incredible bravery through “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of [their lives] above and beyond the call of duty”

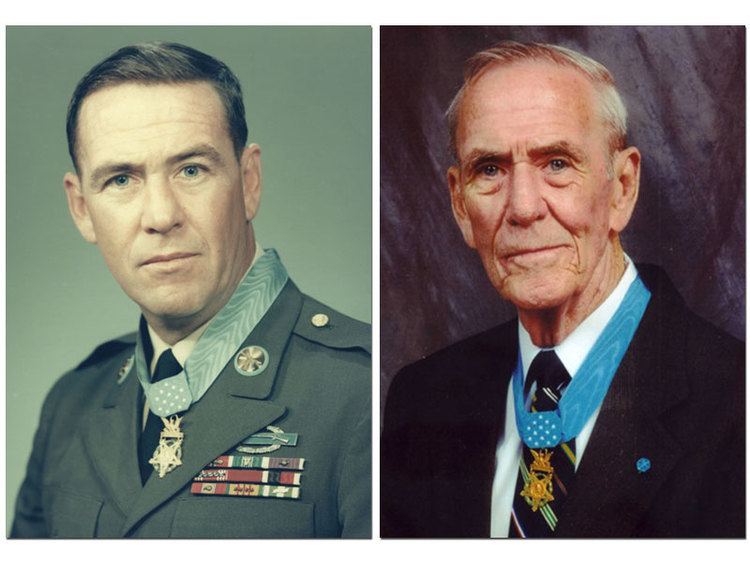

Of the 9 million Americans who were on active duty during the Vietnam War, only 248 Medal of Honors were received, with only 92 being awarded to a living recipient. One of those was awarded to David McNerney, who graduated from St. Thomas Highschool in 1949.

While David McNerney was born in Massachusetts in 1931, he moved to Houston around the age of 10 and would enroll in St. Thomas High School in 1945. He grew up in a family with a decorated military history. His father was a World War 1 veteran who received the Distinguished Service Cross (the nation’s second highest medal for bravery and risk of life, under the Medal of Honor), the Silver Star, and two purple hearts. In addition to his father, McNerney’s brother and sister also served as a submariner and nurse, respectively. This Military legacy inspired McNerney to enlist in the United States Navy after graduating from St. Thomas.

After serving 2 tours of combat in the Korean War, McNerney was discharged in 1952. Following a brief stint at the University of Houston, McNerney reenlisted but this time in the US Army. After joining the army, he volunteered for special warfare and was a part of the first 500 United States soldiers sent to Vietnam as military advisors for the South Vietnamese army. After a second deployment, he was sent back to the states to train soldiers. He was tasked with training Company A of the 1st Battalion in the 8th Infantry Regiment. Originally this job would have had him remain stateside, continuing to train more soldiers

However, his years of experience could not prepare him for the ambush his company would face in March of 1967. A few months after arriving in Vietnam, Company A moved into the Central Highlands, near the Cambodian border. On March 21, McNerny’s company was sent by helicopter into Polei Doc. Polei Doc was part of the Plei Trap Valley, nicknamed the Valley of Tears; this was a part of the Ho Chi Minh trail and contained some of the toughest terrain in Vietnam with steep, jungle covered mountains coupled with a lack of water and an abundance of Northern Vietnamese troops. It was into this valley of Tears that Company A and B entered via helicopter on March 21. They were tasked with searching for a missing reconnaissance patrol. After a night, the two companies split up on March 22.

Almost immediately, Company A was ambushed by a large Northern Vietnamese force totaling almost three times their size. The brutal ambush came from the front of the company, and McNerney was in the back. The Northern Vietnamese were attempting to split up the company. Despite this, McNerney ran immediately to the front, the area of heaviest contact, braving intense gunfire. While helping to fortify the defensive position, he came into close contact with several Northern Vietnamese soldiers, he killed them, but in the confrontation, he was severely injured by a grenade. Despite this, McNerney continued to lead and fight the Vietnamese, assaulting and dismantling a machine gun post that was pinning down soldiers outside of the defensive position. After returning to the position, McNerney learned of the deaths and injuries sustained by the leadership of the company. Immediately he assumed command and ordered artillery fire with 60 feet of himself in a daring effort to repulse the enemy. Due to the thick vegetation, areal support could not locate the company’s position in order to resupply. In order to signal to the helicopters, McNerney climbed a tree that was fully exposed to enemy fire in order to place a marker at the top of it. Next, the company had to clear a zone for the helicopters to land. To do this, McNerney ran outside of the defensive position towards the enemy and their gunfire to retrieve explosives that had been dropped earlier at first contact. He then utilized these explosives to blow up trees, clearing a landing zone. This allowed for medical evacuations for wounded soldiers to occur. McNerney however refused to be evacuated himself despite his injury and continued to lead his company until a new commander arrived the next day.

The ambush was horrific, and A Company lost 22 of the 108 troops along with 42 wounded. However, the leadership, bravery, and selflessness exhibited by McNerney allowed the Company to repel the significantly larger attacking force and saved an untold number of wounded who were able to be evacuated because of his bravery. After the battle, around 400 dead Vietnamese were found. Leonard McElroy, a soldier who fought alongside McNerney described his impact on the battle, saying “there’s a bunch of guys walking around today who wouldn’t be if it wasn’t for him… we treated him like a father.”

McNerney would return from Vietnam later that year and would go on to receive the United States Medal of Honor a year later in 1968 from United States President Lyndon B. Johnson. After earning the medal McNerney returned to Vietnam for his fourth and final tour, retiring afterwards in 1969 as a First Sergeant. Following his retirement he went on to work for the government as a customs inspector in the Port of Houston. He remained active at St. Thomas and donated his Medal of Honor to the school in 2004. While the medal has since been moved to be displayed by his division, a replica is currently displayed at St. Thomas in the Hall of Honor. David McNerney passed away in 2010 at 79 and was buried at the Houston National Cemetery. His bravery and gallantry under the worst of conditions serves as an example to every student at St. Thomas, and will continue to for generations to come.

This is Creighton's first year on staff. He is primarily interested in sports and feature writing. Outside of journalism he plays baseball and is looking...